School of the Arts Institute of Chicago

In-Studio Summer Residency, 2022

The Rest, circa 2021

Ann Wachter

Popcorn, circa 2002

Ann Wachter

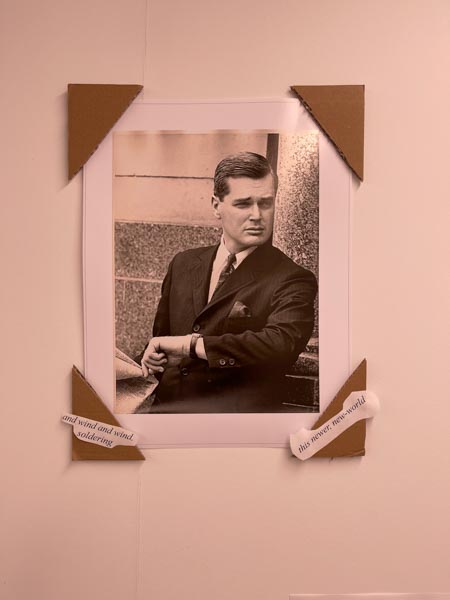

The Watch, circa 1962

photographer unknown

Several months after he passed away, I took up the cause of finding a voice for the elderly. This led to my work titled “A Road Beyond Košice.“ This poem explores erasure — how isolation and financial hardships create a vacuum within which survival is significantly reduced.My poetry draws awareness toward people living on the fringes of society — the poor, the elderly, women without means. Another important undercurrent is about how awareness operates within the schematic of the phases of life we all experience. I deal a lot in persona, but venture into the abstract.

A Road Beyond Košice

Around 2009 I started to collect factual data in all branches of my family tree. My father-in-law survived my mother-in-law (who passed away in 2015) which allowed me to focus as much as I possibly could on his care from a distance of hundreds of miles between Illinois and New York. Howard passed away in 2021, shortly after travel restrictions were lifted— in place (as we all know) because of the COVID-19 pandemic. This poem is my attempt to embody his life. Many apologies for its imperfections.

2017

My daughter-in-law is coming to visit. She filled out an application with the Department of Veterans Affairs for pension benefits. I only served two years. I haven’t worked since 1990 but she assures me I’m eligible. She should give me the pension payments. I could use them.

Here she is. Howard, I already told you, you’re getting the benefits because you need home help. I can’t give the pension to you. It’s for home helpers. Otherwise, they’ll take it away.

I’ll tell you about my life. My efficiency is rent-controlled; for me, it’s a collection of containers — every crevice, suitcase, shelf, a menagerie of memories…

2018

…I order in every day. The Daily Rainbow — Boston Market, Nick’s Pizza, Wing Wah, my local Dinar — I slather mouth-watering morsels in my saliva, swallow them whole.

Howard, you eat too fast. That’s why your esophagus expels up.

You know I divorced Mikki and Judy is gone. I know, she died of Parkinson’s. Do you miss her? Her sons didn’t want me around. Judy told me to move out.

I can’t work. I pay my debts with credit, social security, now my veteran’s pension thanks to you and Rich’s generosity.

I’ve told you about my Twelve-step programs. I have books around here from Debtor’s Anonymous. Why do you keep them? Good question. Maybe somebody else will want to read them.

I plan to marry the love of my life. Hahaha. You always make me laugh when you say that.

The 92nd Street Y is my salvation. When’s the last time you went, Howard?

I take a music class with a lot of women. Every time I go, I sing a new song. Penny always tells me I have a great voice. What are you singing now?

Each time I see a little girl

Of five or six or seven

I can’t resist a joyous urge

To smile and say

Thank heaven for little girls,

Thank Heaven for Little Girls. Every time I sing it, I think of Danielle. Who do you know there? There are three or four ladies who always talk to me. I can’t wait to meet the love of my life.

2019

Howard, I’m so glad you could make it. How was your flight? I’ll take care of your luggage. Come in and sit down. Can I take your jacket?

It’s drafty. I’m cold. I’ll turn the heat up. Would you? That’s nice.

Howard, tell me about your family heritage. Do you have any relatives that live nearby? Do you see anyone?

Everyone’s gone but a couple cousins. I’m so damn cold. Get me my vest. Can you reach it? I love that vest. Red suits me. Yes, it does.

I brought you a few things. See this picture? This man looks like my father. It was taken in Munkacs, Hungary. He spent four years in a Russian prison camp in WWI. When he got out he immigrated to America and married my mother. Her maiden name was Elefant. She cut me. Somehow I forgave her.

Her sister, Ilona, lived in a place called Košice. The Nazis took over and sent her and two of her daughters to Auschwitz. One day earlier, she’d moved her eldest to Budapest to live with her violin instructor. Edith was a prima ballerina forced to dance for that damn Angel of Death. She and Magda, the other daughter, survived the Holocaust. My mother told me she never heard from my aunt again. I’m cold. Throw me my vest. It’s on the chair over there. There.

You asked about Edith’s book. It’s in my suitcase. There. Do you see it? The Choice. Do you want it? There are so many things of mine — photos, slides, brochures, ticket stubs, lists, records — old and brittle, I still want them.

Keepsakes hold good memories, right Howard? They are like companions. Interesting that you say that. I just look at everything. I don’t even know what I have or where it is.

2021

I’m alone. I prefer to lay in my daybed all day. My care giver is coming because my daughter-in-law is too damn anxious about me. My body’s backing up and cutting loose. Then I can’t go at all. I’m calling the ambulance. Where’s my cellphone. Hello…

Two months later…

Hello, Rich, is that you? I need my diaper changed. Call the nurse. The nurse is here to clean me.

It is what it is — a tangle of octopus tentacles whose suctions no longer stick. They shuttle me to and from Long Island Jewish Hospital to a nursing home with bad food. Now where to? Oh, okay, St. Francis. The food is better there. I have to be isolated again?

I’m beginning to recognize confusion — my past, my mother, questions never asked, answers never given — kept, kept kept, kept kept kept. I tuck it away. I wake up from my third nap. I prefer inertia. I should be waited on. I enjoy dwindling at my own pace.

Where am I now? I wonder as I peek under my lids. My son negotiates COVID restrictions, travels back and forth, kept away even when he’s here. I lean up, lie down. It’s dizzying. He can’t help. I can barely stand. My gut hurts. It won’t stop. I’m off IV’s, on again, off again. Pump 3 plasma into me to up my white cell count — one, two, three — back on the IV’s.

They’re here. I don’t believe it. My grandchildren hand feed me Ritz crackers. Take me home now. They laugh. I want to go home. They leave. I’m released to the nursing home, isolated. I awaken in a van in the middle of the street near my apartment. I call my son. It takes awhile, finally registers, My brain is addled. Must be the meds. He calls an orderly to explain where I am.

I find myself meeting my memories as real people in the here and now; wishing I’d read Edith’s book. I should have read it. Choices peer at me into me; glare garish grins. Get me my red vest — it’s somewhere over there.

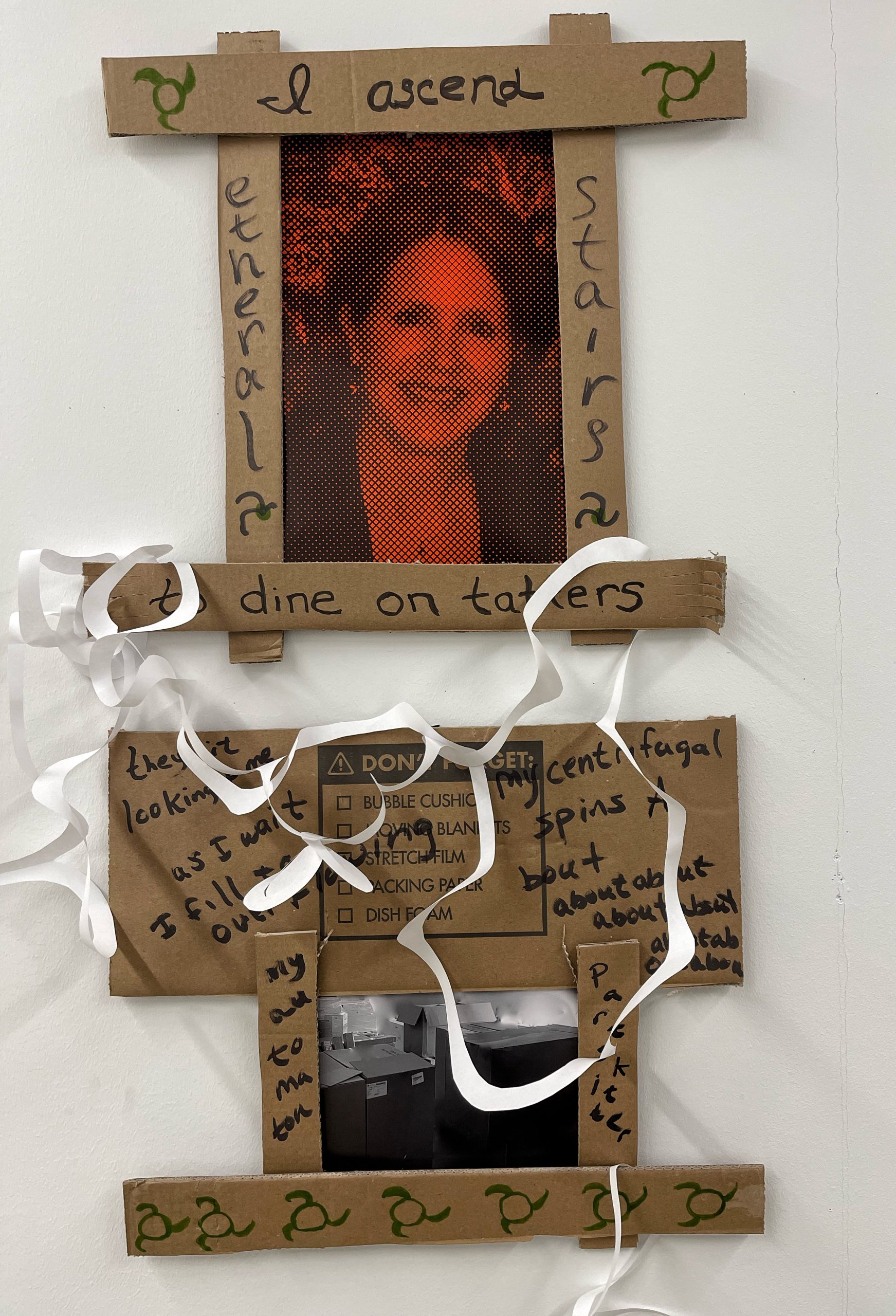

I had an inkling I’d like to experiment with identity as part of my studio investigations so I created this pixilated self-portrait in Photoshop and toyed around with how to adapt it to my ‘empty box’ studio motif.

The main impetus for the idea is derived from a confessional poem titled Triskele, a metaphor for the three legs of life — youth, middle and old age — it represents my life journey and the unforeseen lessons it affords me.

Triskele

My triskele runs on three legs.

Look how dark the third leg, how arthritic, how slow it walks.

I carefully avoid its invariable advancements

Allowing my patience to embrace balance, heal surgical wounds.

I am the pending medicare recipient, a remnant of the half-baked.

I am giving this leg up for placement alongside the other two;

the first leg moved from crawl to walk, the second walk to crawl.

They passed over me like the wind carrying a seed

I held on, forgotten as the middle earth, never trodden.

They brought me to the brink of knowledge, telling me to leap.

I packed my parachute but had no chord to catch —

My scribbled notebooks, full of nonsense, decade’s old;

My husband, gone and children on their own,

Their stores of bounty empty of life’s plenty.

I gasp as my heart fibs, squeezing air

Learning anew, each breath is a slow, deep inhale

Steadying the beat of my drum to a thump, thump, thump —

Oxygen forces meaning between the lines flowing across my page.

I coat my swabs in lemon juice

As I sit praying, hoping their secrets reveal

Knowledge fostered by my fortitude, not their last supper.

Before them was the family of my youth

Through which each breath smelled of tar and nicotine

Not only from menthol’s inhale but each ring’s exhale too.

Upon each grey swirl, my brain lightened its load

Of knowledge which hit upon our painted beige walls, blackened.

One day, I scrubbed off their mediocre melodies,

blowing soapy soot upon the Jesuits who blew them back.

From that day forward, my light flickered about each crawl, each walk

And all I’d yearned for repeated words back, askew —

Ignoring my Sunday rosary beads re-configuring Jesus’s resurrection.

While caressing scribbles upon this or that,

My walk to crawl scurried back.

I stood firmly on my perch to fly God knows where;

So it is on triskele’s third leg, my final breath declares.

My triskelion arrived and went about its Celtic purpose

Uniting my lagging leg with the sinews of my youth and middle age.

Adding value to my coinage, it gave me substance.

Adding weight to my pocket, it gave me depth.

I twirled it on the table and watched it progressively slow and falter.

I caught it, recognizing my role with this renegade survivor,

Both of history and daily living, was insignificant